On Mentorship

What even is mentorship?

Let me start by clarifying some things.

Mentorship is not:

- A manager / subordinate relationship

- A teacher / student relationship

- An experienced person telling a less experienced person what to do

- A disciplinary / punitive process

Mentorship is:

A partnership in which a more experienced person shares their knowledge and skills whilst providing feedback and strategies to aid the mentee's personal and professional growth.

Particularly important is the notion that it is a partnership and that it includes both personal and professional growth. To ignore the personal development would diminish the whole process.

Finding a mentor

Firstly, your manager is not your mentor, they are your manager! That's not to say your manager is not a good person, or that they cannot help you develop, but their primary motivation has to be meeting the needs of the business. You and your development needs may get in the way of that.

Another person who is not your mentor is your friend or family member. Your friends and family are there to have your back, to tell you that everyone else is an asshole and that you are awesome. This is definitely useful from a personal perspective, but it's not useful from a growth perspective.

A good mentor needs to be someone you can trust to tell it like it is, whether you like it or not. They need to be someone who's opinions and skills you respect and who's feedback you can accept and use without feeling inferior or insulted.

Please don't find a mentor who's a technically brilliant asshole. We've all met them, people who really know their stuff, but struggle to be part of a team without being destructive. Your mentor should be a person who can guide your personal growth as well and part of that is about interacting with other people and building relationships.

Look around your organisation for someone who inspires you and reach out to them. Don't be offended if they are unable to mentor you, inspirational people may quickly reach their mentoring capacity! They may know other people to recommend.

Bear in mind that being a good mentor requires time and desire to help. A cold approach (i.e. without any genuine existing relationship) may be rejected, so it's also worth trying to spend time around the potential mentor.

If you can't find someone within your organization, you may be able to find someone through Meetups or your wider social circle.

When you've identified a potential mentor explain to them why you've picked them and what you're looking to work on.

Being a mentor

Being a good mentor requires a bunch of skills and a serious commitment to the development of the mentee. It shouldn't be taken on lightly as half-hearted mentorship can be more detrimental to the recipient than useful.

Skills that will really help with mentoring include:

- Technical competence in the area for development

- Open listening skills

- Action planning skills

- Story telling skills

Things that aren't skills, but are also useful!

- A genuine desire to help the mentee

- The mental strength to give someone feedback that they may not enjoy

- A willingness to share stories of your own failures

If you think that you can be a good mentor, go for it, if not maybe you should look for one yourself!

Being a good mentor is not about being perfect and knowing "all the answers"™. It's all about the partnership, you can learn as much being as mentor and the mentee.

Being a mentee

In order to get the most out of the process, you're gonna need to be a good mentee! So, what does that look like?

A good mentee:

- Accepts feedback, in the spirit it is given

- Is prepared to work hard on the areas that are identified

- Is open and honest

- Is respectful of the time and commitment given to them

- Completes 'tasks' that are agreed upon, diligently, and doesn't make excuses

The may seem a bit 'harsh', but there's serious time and effort being given to you and that has a price. Executive mentors, for example, can attract rates of $100's per hour, so if you can get that 'free' from within your organization, cherish and respect it!

I think most of these points are easily understood, but let me expand on how to accept feedback.

Getting good at feeling uncomfortable

Let me share a story from a mentorship experience I once had.

So I had received some feedback that my behaviour in meetings was basically pissing people off. I talked too much and too forcefully. I was horrified, couldn't people see how enthusiastic I was about the topic?, couldn't they see how I wanted to improve the world?

This feedback was a powerful fork in the road. I could give them the metaphorical middle finger, ignore the feedback and retreat into righteous indignation vowing never to change. Alternatively, I could accept the feedback in the sprit it was given (to help me). I could swallow down the hurt that the feedback caused (and it did hurt) and do something about it.

The best feedback is often the feedback that makes you feel sick, because it hits a nerve, causing you to question some things you may fundamentally believe or value about yourself. Now I'm not suggesting that you should give up things that are really important to you, reducing yourself to the blandest, most widely palatable version of you. That would be a travesty, but there is a middle ground to be struck and that's the place where really good stuff happens.

I really value being enthusiastic about things and I value debating the big stuff, so how could this be reconciled with the feedback? How to fix this without giving up 'me'?

I spent time discussing it with my mentor, openly and honestly. She was able to help me understand that it was rarely the content of what I was saying and more that I was inept at picking social cues that I'd made my point and it was time to shut up! I could keep my enthusiasm, but would be more able to influence actual change if I could modify my approach. We agreed on a strategy, we'd sit next to each other in meetings and she'd kick me under the table if I was going too far! On receiving the cue, I would wind up what I was saying, but I would look around the room to pick up on people's body language and the mood. Afterwards she'd ask me how I thought it went and give me feedback on the cues she saw that I may have missed. This led to very rapid changes to my approach. I was recognizing social cues that I didn't even know existed and this knowledge actually increased my ability to influence because I was pissing fewer people off!

What I'm really trying to get at here, is that feedback is uncomfortable, it challenges the things we know and believe about ourselves. It takes practice and patience to get good at receiving feedback and some days, you maybe just shouldn't open up for feedback! When you start the process, I encourage you to tackle small things first, get familiar with the process. Knowing what to expect will make it less scary, but probably not less uncomfortable.

Moving from the unknown to the known

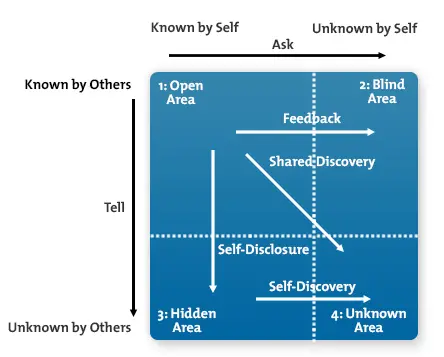

You may or may not have heard of the Johari window. It's a framework for describing our view of ourselves in relation to the view of others.

The image below shows this visually 1.

So the Open Area is that which know by you and known by others, it's your public persona. It's the bit that you're happy to share with the world. You would also likely be familiar with the Hidden Area - the bits of yourself that you know, but you don't openly share with others. These things generally become known if you choose to disclose them. The Unknown Area describes things that neither you nor others know about you, things that will present themselves given a triggering situation.

The part of most interest in a mentoring relationship is the Blind Area - that which is known to others, but not yourself. This is where a trusted mentor can point things out to you and bring it to your awareness. This is the part that's uncomfortable because it can challenge some of our core beliefs and assumptions about ourselves.

As a mentor, bringing the Blind Area to awareness can very direct, like giving a specific point of feedback. It can also take the form of an exploratory conversation and clarifying questions. Insights that are arrived at by the mentee when guided this way can be particularly powerful.

A simple plan

I think, broadly, there are four steps to a mentoring session (after the first one), guided by the mentor.

First Meeting

- Understanding

- Challenging

- Planning

Subsequent

- Reviewing

- Understanding

- Challenging

- Planning

The first time you meet, you're gonna need to spend the most time understanding. Avoid the temptation to jump into a solution as soon as a topic presents itself, instead ask questions and clarify your understanding. Ask why?, why should that be?, why do you think that's the case? As you develop your understanding of the issues can you see a blindspot? What is the question that would help the mentee see a new perspective?

Take this simplified exchange.

Mentee: "I don't seem to be getting on very well with Dave."

Mentor:"Oh, what makes you think that?"

Mentee: "Hmm, well I never really feel very comfortable talking to him and Jane told me that he finds me a bit distant."

Mentor:"What do you think would lead Dave to feel that?"

Mentee: "I don't know."

Mentor:"OK, so tell me about the last conversation you had with him."

Mentee: "Well, we chatted very briefly about the project, he told me that he was finding it difficult to keep up."

Mentor:"How did you respond to that?"

Mentee: "I told him that we all feel like that."

Mentor:"How do you think that made Dave feel?"

Mentee: "I'm not sure."

Mentor:"OK, do you think that Dave felt valued?"

Mentee: "Well I did tell him that everyone felt that way, so ... hmm ... actually, no, he probably felt a bit dismissed."

Mentor:"What makes you say that?"

Mentee: "Well if that was me, I'd be like, I don't care that everyone feels like that, I want to talk about how I feel!"

Mentor:"OK, well sounds like there are some things that could be done to change your relationship with Dave."

The important thing of note in this exchange is that rather than jumping into, how can you fix your relationship with Dave, the mentor asked exploratory questions and challenged the mentee's perspective - "do you think that Dave felt valued?".

Now that there is a realisation that things could be different, it's worth a bit of planning of how to fix it and also a deeper exploration of why the mentee was dismissive. Maybe this leads to a story about how the mentor used to think that just chatting with people was a waste of time, but found that if they took a genuine interest in how people felt and what was going on for them, that their relationships were much stronger. It wasn't a case of gossiping, it was about investing in a shared experience, which showed the team that caring for each other was a good thing.

Now we might set a homework task, like "for the next week chat with Dave and get to know a bit more about him".

At the next catch up, in review, you chat about how the homework task has been going.

Mentor: "So, how did you find the homework?"

Mentee: "Well, at first it felt really forced, like I was just trying too hard. I stuck with it though and by Wednesday I found out that we both really like watching {insert popular TV show}. From there it's become much easier to talk and we've got a bunch of common interests. I actually felt really bad about being so dismissive when he raised feeling like he couldn't keep up. I apologized and asked him how he was feeling. He told me not to worry about it, but I could see that he was really pleased I apologized. He then told me about some things that were worrying him on the project, I couldn't fix any of them, but at least I listened. I really feel way better about our relationship and I feel like I now actually care about what happens to him."

Treating the process like a little experiment can be a very powerful way to detach from the immediate discomfort involved in changing behaviour.

Trying something and iterating on it, consciously reflecting on how it went and how it could be better helps to change our behaviour in a really genuine and lasting way.

Although the examples I've given may seem a bit simplistic, they are a distilled version of a real scenarios, with bits changed to protect the innocent :)

It's all about the relationship

Now I could go into a whole range of different techniques for a mentoring relationship, but I think that it's the process of reflection, driven by a trusting relationship that is more valuable than any individual technique.

If there is a true, mutual desire to learn and grow, you'll work it out.

Happy mentoring!